------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Evangelos Venetis: Oil and Diplomacy – Reviewing Greek-Iranian Relations

February 23, 2012 | Evangelos Venetis |

A few days ago the Iranian Foreign Ministry called the Ambassador of Greece in Tehran, along with five other counterparts of the EU countries, to notify him that Tehran intends to change its oil supply conditions to Athens. Two hours later the Iranian Oil Ministry announced that it does not intend to cut off oil supplies to both Greece and the other five EU countries. In the meantime the price of crude had risen by two dollars. But after a few days Tehran made a surprising, but of minor economic importance move, by officially announcing the discontinuation of oil sales to Britain and France. This move left open the possibility of interruption or reduction for Iranian oil in Greece. [More »]

| Share This..83 |

Pavlos Efthymiou: ‘Can One Save the Titanic? From the Memorandum, Back to Growth Again’ – Book Review*

February 8, 2012 | Pavlos Efthymiou |

Nikos Christodoulakis, Professor of Economic Analysis at the Athens University of Economics and Business (AUEB), reviews, in this second edition of “Can One Save the Titanic”, the preeminent debates surrounding the Eurozone crisis and particularly the options available to Greece and its partners to overcome it[1]. The book begins with a pre-emptive strike against one [...]

[More »] | Evangelos Venetis: The EU oil ban and the regime change in Iran

February 14, 2012 | Evangelos Venetis | (1)

The above question has been looming over relations between Iran and the EU since the 1979 Islamic Revolution. The EU foreign policy, which has been actually a desideratum, has kept ever since a cautiously neutral stance toward the Islamic Republic. In spite of the appointment of the Baroness Kathrin Ashton as the EU High Representative [...]

[More »] | Global Affairs ForumInterview with Dr. Ibrahim Kalin, 8/10/2010, “Greek-Turkish relations: current status, future prospects”, 08/10/2010Interview with Prof. Menachem Klein – “The new round of peace talks between Israelis and Palestinians: Is there any hope for progress?”The resolution of the FYROM name issue

[View All]

|

Bledar Feta: The Janus face of the Albanian politics

February 8, 2012 | ELIAMEP |

Albania has just entered its 100th year of independence. But does the internal political scene offer enough reasons for celebration? The picture is mixed. On the one hand the country has experienced almost two years of bifurcation and polarization of the political space that endangered social stability. The country experienced successive waves of political standoffs, [...]

[More »] | Harris Mylonas and Emirhan Yorulmazlar: Regional multilateralism – The next paradigm in global affairs*

January 23, 2012 | ELIAMEP |

The Cold War and the early post-Cold War periods were relatively easy to define and comprehend. The first was roughly the struggle between two superpowers forming a bipolar system where almost every state had to choose a side. What followed was a period described by Fukuyama as “The End of History” announcing the triumph of [...]

[More »] |

Pavlos Efthymiou: The Diary of the Crisis – Book Review*

January 29, 2012 | Pavlos Efthymiou |

Leading Greek journalist Pavlos Tsimas (Mega, Ta Nea) narrates in the first person, his experiences and reflections on the global economic crisis drawing from his interview material, images and memories. ‘The diary’ is a story of bubbles, irresponsible deregulation, irresponsible lending and borrowing and unrestrained speculation. It assesses government responsibility, greed and revisits the Keynesian/Monetarist [...]

[More »] | Konstantinos Makris: Research – Re-use plastic water containers

November 15, 2011 | Makris Konstantinos |

Increasing consumption of water packaged in plastic containers in Cypriot and other Mediterranean countries continues to compete with tap water for the most popular water source of potable use, cooking, and beverage preparations (cold/hot coffee, tea and juices). A general notion in the Cypriot society calls for precautionary measures against packaged water quality deterioration during [...]

[More »] |

======================================================================

Acropolis of Athens

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Acropolis of Athena * | |

|---|---|

| |

| Country | Greece |

| Type | Cultural Landmark built before perspective time. |

| Criteria | i, ii, iii, iv, vi |

| Reference | 404 |

| Region ** | Europe |

| Coordinates | 37.971421°N 23.726166°E |

| Inscription history | |

| Inscription | 1987 (11th Session) |

| * Name as inscribed on World Heritage List ** Region as classified by UNESCO | |

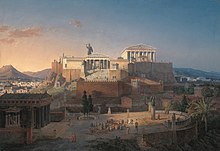

The Acropolis of Athens or Citadel of Athens is the best known acropolis (Gr. akros, akron,[1] edge, extremity + polis, city, pl. acropoleis) in the world. Although there are many other acropoleis in Greece, the significance of the Acropolis of Athens is such that it is commonly known as The Acropolis without qualification. The Acropolis was formally proclaimed as the preeminent monument on the European Cultural Heritage list of monuments on 26 March 2007.[2] The Acropolis is a flat-topped rock that rises 150 m (490 ft) above sea level in the city of Athens, with a surface area of about 3 hectares. It was also known asCecropia, after the legendary serpent-man, Cecrops, the first Athenian king.

Contents[hide] |

[edit]

History

[edit]

Early settlement

While the earliest artifacts date to the Middle Neolithic era, there have been documented habitations in Attica from the Early Neolithic (6th millennium BC). There is little doubt that aMycenaean megaron stood upon the hill during the late Bronze Age.[citation needed] Nothing of thismegaron survives except, probably, a single limestone column-base and pieces of several sandstone steps. Soon after the palace was constructed, a Cyclopean massive circuit wall was built, 760 meters long, up to 10 meters high, and ranging from 3.5 to 6 meters thick. This wall would serve as the main defense for the acropolis until the 5th century.[3] The wall consisted of twoparapets built with large stone blocks and cemented with an earth mortar called emplekton (Greek: ἔμπλεκτον).[4] The wall follows typical Mycenaean convention in that it followed the natural contour of the terrain and its gate was arranged obliquely, with a parapet and tower overhanging the incomers' right-hand side, thus facilitating defense. There were two lesser approaches up the hill on its north side, consisting of steep, narrow flights of steps cut in the rock. Homer is assumed to refer to this fortification when he mentions the "strong-built House of Erechtheus" (Odyssey 7.81). At some point before the 13th century an earthquake caused a fissure near the northeastern edge of the acropolis. This fissure extended some thirty five meters to a bed of soft marl in which a well was dug.[5] An elaborate set of stairs were built and the well served as an invaluable, protected source of drinking water during times of siege for some portion of the Mycenaean period.

[edit]

The Dark Ages

There is no conclusive evidence for the existence of a Mycenean palace on top of the Athenian Acropolis. However, if there was such a palace, it seems to have been supplanted by later building activity on the Acropolis. Not much is known as to the architectural appearance of the Acropolis until the archaic era. In the 7th and the 6th centuries BC[6], the site was taken over by Kylon during the failed Kylonian revolt, and twice byPisistratus: all attempts directed at seizing political power by coups d' etat. Nevertheless, it seems that a nine-gate wall, the Enneapylon, had been built around the biggest water spring, the "Clepsydra", at the northwestern foot.

[edit]

Archaic Acropolis

A temple sacred to "Athena Polias" (Protectress of the City) was quickly erected by mid-6th century BC. This Doric limestone building, from which many relics survive, is referred to as the "Bluebeard" temple, named after the pedimental three-bodied man-serpent sculpture, whose beards were painted dark blue. Whether this temple replaced an older one, or a mere sacred precinct or altar, is not known. In the late 6th century BC yet another temple was built, usually referred to as the Archaios Naos (Old Temple). This temple of Athena Polias was built upon theDoerpfeld foundations.[7] It is unknown where the "Bluebeard" temple was built. There are two popular theories (1) the "Bluebeard" temple was built upon the Doerpfeld foundations, (2) the "Bluebeard" temple was built where the Parthenon now stands.[8] That being said it is unknown if the "Bluebeard" temple and the Archaios Naos coexisted.

To confuse matters, by the time the "Bluebeard" Temple had been dismantled, a newer and grander marble building, the "Older Parthenon" (often called the "Ur-Parthenon", German for "Early Parthenon"), was started following the victory at Marathon in 490 BC. To accommodate it, the south part of the summit was cleared of older remnants, made level by adding some 8,000 two-ton blocks of Piraeus limestone, a foundation 11 m (36 ft) deep at some points, and the rest filled with earth kept in place by the retaining wall.

The Older Parthenon was still under construction when the Persians sacked the city in 480 BC. The building was burned and looted, along with the Archaios Naos and practically everything else on the rock. After the Persian crisis had subsided, the Athenians incorporated many of the unfinished temple's architectural members (unfluted column drums, triglyphs, metopes, etc.) into the newly built northern curtain wall of the Acropolis, where they serve as a prominent "war memorial" and can still be seen today. The devastated site was cleared of debris. Statuary, cult objects, religious offerings and unsalvageable architectural members were buried ceremoniously in several deeply dug pits on the hill, serving conveniently as a fill for the artificial plateau created around the classic Parthenon. This "Persian debris" is the richest archaeological deposit excavated on the Acropolis.

[edit]

The Periclean building program

Most of the major temples were rebuilt under the leadership of Pericles during the Golden Age of Athens (460–430 BC). Phidias, a great Athenian sculptor, and Ictinus and Callicrates, two famous architects, were responsible for the reconstruction. During the 5th century BC, the Acropolis gained its final shape. After winning at Eurymedon in 468 BC, Cimon and Themistocles ordered the reconstruction of southern and northern walls, and Pericles entrusted the building of the Parthenonto Ictinus and Callicrates.

In 437 BC, Mnesicles started building the Propylaea, monumental gates with columns of Pentelicmarble, partly built upon the old propylaea of Pisistratus. These colonnades were almost finished in 432 BC and had two wings, the northern one serving as picture gallery. At the same time, south of the propylaea, building of the small Ionic Temple of Athena Nike commenced. After an interruption caused by the Peloponnesian War, the temple was finished in the time of Nicias' peace, between 421 BC and 415 BC.

During the same period as the building of the Erechtheum, a combination of sacred precincts including the temples of Athena Polias, Poseidon, Erechtheus, Cecrops, Herse, Pandrosos andAglauros, with its so-called the Kore Porch (or Caryatids' balcony), was begun.

Between the temple of Athena Nike and the Parthenon, there was the temenos of Artemis Brauronia or Brauroneion, the goddess represented as a bear and worshipped in the deme of Brauron. The archaic xoanon of the goddess and a statue made by Praxiteles in the 4th century BC were both in the sanctuary.

Behind the Propylaea, Phidias' gigantic bronze statue of Athena Promachos ("she who fights in the front line"), built between 450 BC and 448 BC, dominated. The base was 1.50 m (4 ft 11 in) high, while the total height of the statue was 9 m (30 ft). The goddess held a lance whose gilt tip could be seen as a reflection by crews on ships rounding Cape Sounion, and a giant shield on the left side, decorated by Mys with images of the fight between the Centaurs and the Lapiths. Other monuments that have left almost nothing visible to the present day are the Chalkotheke, the Pandroseion, Pandion's sanctuary, Athena's altar, Zeus Polieus's sanctuary and, from Roman times, the circular temple of Augustus andRome.

[edit]

Hellenistic and Roman period

During the Hellenistic and Roman periods, many of the existing buildings in the area of the Acropolis were repaired, due to damage from age, and occasionally, war.[9] Monuments to foreign kings were erected, notably those of the Attalid kings of Pergamon Attalos II (in front of the NW corner of the Parthenon), and Eumenes II, in front of the Propylaia. These were rededicated during the early Roman Empire to Augustus or Claudius (uncertain), and Agrippa, respectively.[10] Eumenes was also responsible for constructing a stoa on the South slope, not unlike that ofAttalos in the Agora below.

During the Julio-Claudian period, the Temple of Rome and Augustus, a small, round edifice, about 23 meters from the Parthenon, was to be the last significant ancient construction on the summit of the rock.[11] Around the same time, on the North slope, in a cave next to the one dedicated to Pan since the classical period, a sanctuary was founded where the archons dedicated to Apollo on taking office.[12] In the following century, on the South slope, Herodes Atticus built his grand odeon.

[edit]

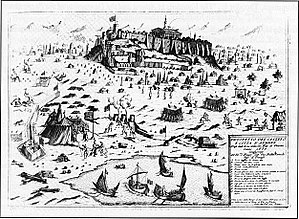

Byzantine, Latin and Ottoman period

In the Byzantine period, the Parthenon was turned into a church, dedicated to theVirgin Mary. Under the Latin Duchy of Athens, the Acropolis functioned as the city's administrative center, with the Parthenon as its cathedral, and the Propylaia as part of the Ducal Palace. A large tower was added, the "Frankopyrgos" (Tower of the Franks), demolished in the 19th century.

After the Ottoman conquest of Greece, the Parthenon was used as the garrison headquarters of the Turkish army,[13] and the Erechtheum was turned into theGovernor's private Harem. The buildings of the Acropolis suffered significant damage during the 1687 siege by the Venetians in the Morean War. The Parthenon, which was being used as a gunpowder magazine, was hit by artillery fire and severely damaged.

In subsequent years, the Acropolis was a site of bustling human activity with many Byzantine, Frankish, and Ottoman structures. The dominant feature during the Ottoman period was a mosque inside the Parthenon, complete with a minaret. Following the Greek War of Independence, most post-Byzantine features were cleared from the site as part of a Hellenizing project that swept the new nation-state.

[edit]

Archaeological remains

The entrance to the Acropolis was a monumental gateway called the Propylaea. To the south of the entrance is the tiny Temple of Athena Nike. A bronze statue of Athena, sculpted by Phidias, originally stood at its centre. At the centre of the Acropolis is the Parthenon or Temple of Athena Parthenos (Athena the Virgin). East of the entrance and north of the Parthenon is the temple known as the Erechtheum. South of the platform that forms the top of the Acropolis there are also the remains of an outdoor theatre called Theatre of Dionysus. A few hundred metres away, there is the now partially reconstructed Theatre of Herodes Atticus.

All the valuable ancient artifacts are situated in the Acropolis Museum, which resides on the southern slope of the same rock, 280 metres from the Parthenon.

[edit]

Site plan

Site plan of the Acropolis at Athens showing the major archaeological remains

- Parthenon

- Old Temple of Athena

- Erechtheum

- Statue of Athena Promachos

- Propylaea

- Temple of Athena Nike

- Eleusinion

- Sanctuary of Artemis Brauronia or Brauroneion

- Chalkotheke

- Pandroseion

- Arrephorion

- Altar of Athena

- Sanctuary of Zeus Polieus

- Sanctuary of Pandion

- Odeon of Herodes Atticus

- Stoa of Eumenes

- Sanctuary of Asclepius orAsclepieion

- Theatre of Dionysus Eleuthereus

- Odeon of Pericles

- Temenos of Dionysus Eleuthereus

- Aglaureion

[edit]

The Acropolis Restoration Project

The Project began in 1975 and is now nearing completion. The aim of the restoration was to reverse the decay of centuries of attrition, pollution, destruction by acts of war, and misguided past restorations. The project included collection and identification of all stone fragments, even small ones, from the Acropolis and its slopes and the attempt was made to restore as much as possible using reassembled original material - with new marble from Mount Penteli used sparingly. All restoration was made using titanium dowels and is designed to be completely reversible, in case future experts decide to change things. A combination of cutting-edge modern technology and extensive research and reinvention of ancient techniques were used.

The Parthenon colonnades, largely destroyed by Venetian bombardment in the 17th century, were restored, with many wrongly assembled columns now properly placed. The roof and floor of the Propylaea were partly restored, with sections of the roof made of new marble and decorated with blue and gold inserts, as in the original. The temple of Athena Nike is the only edifice still unfinished, pending proper reassembly of its parts, all of which survive practically intact.

A total of 2,675 tons of architectural members were restored, with 686 stones reassembled from fragments of the originals, 905 patched with new marble, and 186 parts made entirely of new marble. A total of 530 cubic meters of new Pentelic marble were used.

[edit]

Cultural significance

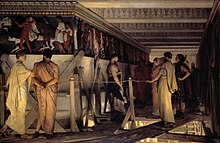

Every four years, the Athenians held a festival called the Panathenaea that rivalled the Olympic Games in popularity. During the festival, a procession moved through Athens up to the Acropolis and into the Parthenon (Suggested to be depicted on the Parthenon frieze). There, a vast robe of woven wool (peplos) was ceremoniously placed on Phidias' massive ivory and gold statue of Athena.

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Pericles

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

This article is about the Greek statesman. For other uses, see Pericles (disambiguation). For other persons named Perikles, see Perikles (given name).

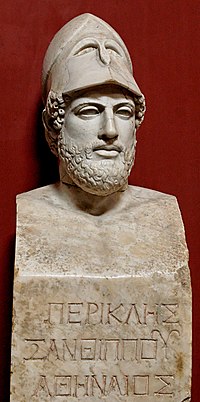

| Pericles | |

|---|---|

Bust of Pericles bearing the inscription “Pericles, son of Xanthippus, Athenian”. Marble, Roman copy after a Greek original from ca. 430 BC | |

| Born | ca. 495 BC Athens |

| Died | 429 BC Athens |

| Allegiance | Athens |

| Rank | General (Strategos) |

| Battles/wars | Battle in Sicyon and Acarnania (454 BC) Second Sacred War (448 BC) Expulsion of barbarians from Gallipoli (447 BC) Samian War (440 BC) Siege of Byzantium (438 BC) Peloponnesian War (431–429 BC) |

Pericles (Greek: Περικλῆς, Periklēs, "surrounded by glory"; c. 495 – 429 BC) was a Greek prominent and influential statesman, orator, and general of Athens during the city's Golden Age—specifically, the time between the Persian and Peloponnesianwars. He was descended, through his mother, from the powerful and historically influential Alcmaeonid family.

Pericles had such a profound influence on Athenian society that Thucydides, his contemporary historian, acclaimed him as "the first citizen of Athens". Pericles turned the Delian League into an Athenian empire and led his countrymen during the first two years of the Peloponnesian War. The period during which he led Athens, roughly from 461 to 429 BC, is sometimes known as the "Age of Pericles", though the period thus denoted can include times as early as the Persian Wars, or as late as the next century.

Pericles promoted the arts and literature; this was a chief reason Athens holds the reputation of being the educational and cultural centre of the ancient Greek world. He started an ambitious project that generated most of the surviving structures on theAcropolis (including the Parthenon). This project beautified the city, exhibited its glory, and gave work to the people.[1] Furthermore, Pericles fostered Athenian democracy to such an extent that critics call him a populist.[2][3]

Contents[hide] |

[edit]

Early years

Pericles was born c. 495 BC, in the deme of Cholargos just north of Athens.α[›] He was the son of the politician Xanthippus, who, althoughostracized in 485–484 BC, returned to Athens to command the Athenian contingent in the Greek victory at Mycale just five years later. Pericles' mother, Agariste, a scion of the powerful and controversial noble family of the Alcmaeonidae, and her familial connections played a crucial role in starting Xanthippus' political career. Agariste was the great-granddaughter of the tyrant of Sicyon, Cleisthenes, and the niece of the supreme Athenian reformer Cleisthenes, another Alcmaeonid.β[›][4] According to Herodotus and Plutarch, Agariste dreamed, a few nights before Pericles' birth, that she had borne a lion.[5][6] One interpretation of the anecdote treats the lion as a traditional symbol of greatness, but the story may also allude to the unusual size of Pericles' skull, which became a popular target of contemporary comedians (who called him "Squill-head", after theSquill or Sea-Onion).[6][7] (Although Plutarch claims that this deformity was the reason that Pericles was always depicted wearing a helmet, this is not the case; the helmet was actually the symbol of his official rank as strategos (general)).[8]

| "Our polity does not copy the laws of neighboring states; we are rather a pattern to others than imitators ourselves. It is called a democracy, because not the few but the many govern. If we look to the laws, they afford equal justice to all in their private differences; if to social standing, advancement in public life falls to reputation for capacity, class considerations not being allowed to interfere with merit; nor again does poverty bar the way, if a man is able to serve the state, he is not hindered by the obscurity of his condition." |

| Pericles' Funeral Oration as recorded by Thucydides,2.37γ[›]; Thucydides disclaims verbal accuracy. |

His family's nobility and wealth allowed him to fully pursue his inclination toward education. He learned music from the masters of the time (Damon or Pythocleides could have been his teacher)[10][11] and he is considered to have been the first politician to attribute great importance to philosophy.[9] He enjoyed the company of the philosophers Protagoras, Zeno of Elea andAnaxagoras. Anaxagoras in particular became a close friend and influenced him greatly.[10][12] Pericles' manner of thought and rhetorical charisma may have been in part products of Anaxagoras' emphasis on emotional calm in the face of trouble and skepticism about divine phenomena.[4] His proverbial calmness and self-control are also regarded as products of Anaxagoras' influence.[13]

[edit]

Political career until 431 BC

[edit]

Entering politics

In the spring of 472 BC, Pericles presented the Persae of Aeschylus at the Greater Dionysia as a liturgy, demonstrating that he was one of the wealthier men of Athens.[4] Simon Hornblower has argued that Pericles' selection of this play, which presents a nostalgic picture of Themistocles' famous victory at Salamis, shows that the young politician was supporting Themistocles against his political opponent Cimon, whose faction succeeded in having Themistocles ostracized shortly afterwards.[14]

Plutarch says that Pericles stood first among the Athenians for forty years.[15] If this was so, Pericles must have taken up a position of leadership by the early 460s BC- in his early or mid thirties. Throughout these years he endeavored to protect his privacy and tried to present himself as a model for his fellow citizens. For example, he would often avoid banquets, trying to be frugal.[16][17]

[edit]

Ostracizing Cimon

Around 461 BC, the leadership of the democratic party decided it was time to take aim at the Areopagus, a traditional council controlled by the Athenian aristocracy, which had once been the most powerful body in the state.[20] The leader of the party and mentor of Pericles, Ephialtes, proposed a sharp reduction of the Areopagus' powers. The Ecclesia (the Athenian Assembly) adopted Ephialtes' proposal without strong opposition.[17] This reform signalled the commencement of a new era of "radical democracy".[20] The democratic party gradually became dominant in Athenian politics and Pericles seemed willing to follow a populist policy in order to cajole the public. According to Aristotle, Pericles' stance can be explained by the fact that his principal political opponent, Cimon, was rich and generous, and was able to secure public favor by lavishly bestowing his sizable personal fortune.[18] The historian Loren J. Samons II argues, however, that Pericles had enough resources to make a political mark by private means, had he so chosen.[21]

Even after Cimon's ostracism, Pericles continued to espouse and promote a populist social policy.[17] He first proposed a decree that permitted the poor to watch theatrical plays without paying, with the state covering the cost of their admission. With other decrees he lowered the property requirement for the archonship in 458–457 BC and bestowed generous wages on all citizens who served as jurymen in the Heliaia (the supreme court of Athens) some time just after 454 BC.[23] His most controversial measure, however, was a law of 451 BC limiting Athenian citizenship to those of Athenian parentage on both sides.[24]

| "Rather, the admiration of the present and succeeding ages will be ours, since we have not left our power without witness, but have shown it by mighty proofs; and far from needing a Homer for our panegyrist, or other of his craft whose verses might charm for the moment only for the impression which they gave to melt at the touch of fact, we have forced every sea and land to be the highway of our daring, and everywhere, whether for evil or for good, have left imperishable monuments behind us." |

| Pericles' Funeral Oration as recorded by Thucydides (II, 41) γ[›] |

Such measures impelled Pericles' critics to regard him as responsible for the gradual degeneration of the Athenian democracy. Constantine Paparrigopoulos, a major modern Greek historian, argues that Pericles sought for the expansion and stabilization of all democratic institutions.[25] Hence, he enacted legislation granting the lower classes access to the political system and the public offices, from which they had previously been barred on account of limited means or humble birth.[26] According to Samons, Pericles believed that it was necessary to raise the demos, in which he saw an untapped source of Athenian power and the crucial element of Athenian military dominance.[27](The fleet, backbone of Athenian power since the days of Themistocles, was manned almost entirely by members of the lower classes.[28])

Cimon, on the other hand, apparently believed that no further free space for democratic evolution existed. He was certain that democracy had reached its peak and Pericles' reforms were leading to the stalemate of populism. According to Paparrigopoulos, history vindicated Cimon, because Athens, after Pericles' death, sank into the abyss of political turmoil and demagogy. Paparrigopoulos maintains that an unprecedented regression descended upon the city, whose glory perished as a result of Pericles' populist policies.[25] According to another historian, Justin Daniel King, radical democracy benefited people individually, but harmed the state.[29] On the other hand, Donald Kagan asserts that the democratic measures Pericles put into effect provided the basis for an unassailable political strength.[30] After all, Cimon finally accepted the new democracy and did not oppose the citizenship law, after he returned from exile in 451 BC.[31]

[edit]

Leading Athens

Ephialtes' murder in 461 BC paved the way for Pericles to consolidate his authority.δ[›] Lacking any robust opposition after the expulsion of Cimon, the unchallengeable leader of the democratic party became the unchallengeable ruler of Athens. He remained in power almost uninterruptedly until his death in 429 BC.

[edit]

First Peloponnesian War

Main article: First Peloponnesian War

Pericles made his first military excursions during the First Peloponnesian War, which was caused in part by Athens' alliance with Megara and Argos and the subsequent reaction of Sparta. In 454 BC he attacked Sicyon and Acarnania.[32] He then unsuccessfully tried to take Oeniadea on theCorinthian gulf, before returning to Athens.[33] In 451 BC, Cimon is said to have returned from exile and negotiated a five years' truce with Sparta after a proposal of Pericles, an event which indicates a shift in Pericles' political strategy.[34] Pericles may have realized the importance of Cimon's contribution during the ongoing conflicts against the Peloponnesians and the Persians. Anthony J. Podlecki argues, however, that Pericles' alleged change of position was invented by ancient writers to support "a tendentious view of Pericles' shiftiness".[35]

Plutarch states that Cimon struck a power-sharing deal with his opponents, according to which Pericles would carry through the interior affairs and Cimon would be the leader of the Athenian army, campaigning abroad.[36] If it was actually made, this bargain would constitute a concession on Pericles' part that he was not a great strategist. Kagan believes that Cimon adapted himself to the new conditions and promoted a political marriage between Periclean liberals and Cimonian conservatives.[31]

In the mid 450s the Athenians launched an unsuccessful attempt to aid an Egyptian revolt against Persia, which led to a prolonged siege of a Persian fortress in the Nile Delta. The campaign culminated in a disaster on a very large scale; the besieging force was defeated and destroyed.[37] In 451–450 BC the Athenians sent troops to Cyprus. Cimon defeated the Persians in the Battle of Salamis-in-Cyprus, but died of disease in 449 BC. Pericles is said to have initiated both expeditions in Egypt and Cyprus,[38] although some researchers, such as Karl Julius Beloch, argue that the dispatch of such a great fleet conforms with the spirit of Cimon's policy.[39]

Complicating the account of this complex period is the issue of the Peace of Callias, which allegedly ended hostilities between the Greeks and the Persians. The very existence of the treaty is hotly disputed, and its particulars and negotiation are equally ambiguous.[40] Ernst Badian believes that a peace between Athens and Persia was first ratified in 463 BC (making the Athenian interventions in Egypt and Cyprus violations of the peace), and renegotiated at the conclusion of the campaign in Cyprus, taking force again by 449–448 BC.[41] John Fine, on the other hand, suggests that the first peace between Athens and Persia was concluded in 450–449 BC, as a result of Pericles' strategic calculation that ongoing conflict with Persia was undermining Athens' ability to spread its influence in Greece and the Aegean.[40] Kagan believes that Pericles used Callias, a brother-in-law of Cimon, as a symbol of unity and employed him several times to negotiate important agreements.[42]

In the spring of 449 BC, Pericles proposed the Congress Decree, which led to a meeting ("Congress") of all Greek states in order to consider the question of rebuilding the temples destroyed by the Persians. The Congress failed because of Sparta's stance, but Pericles' real intentions remain unclear.[43] Some historians think that he wanted to prompt some kind of confederation with the participation of all the Greek cities; others think he wanted to assert Athenian pre-eminence.[44] According to the historian Terry Buckley the objective of the Congress Decree was a new mandate for the Delian League and for the collection of "phoros" (taxes).[45]

| "Remember, too, that if your country has the greatest name in all the world, it is because she never bent before disaster; because she has expended more life and effort in war than any other city, and has won for herself a power greater than any hitherto known, the memory of which will descend to the latest posterity." |

| Pericles' Third Oration according to Thucydides (II, 64) γ[›] |

During the Second Sacred War Pericles led the Athenian army against Delphiand reinstated Phocis in its sovereign rights on the oracle.[46] In 447 BC Pericles engaged in his most admired excursion, the expulsion of barbarians from the Thracian peninsula of Gallipoli, in order to establish Athenian colonists in the region.[4][47] At this time, however, Athens was seriously challenged by a number of revolts among its allies (or, to be more accurate, its subjects). In 447 BC the oligarchs of Thebes conspired against the democratic faction. The Athenians demanded their immediate surrender, but, after the Battle of Coronea, Pericles was forced to concede the loss of Boeotia in order to recover the prisoners taken in that battle.[9] With Boeotia in hostile hands, Phocis and Locris became untenable and quickly fell under the control of hostile oligarchs.[48] In 446 BC, a more dangerous uprising erupted. Euboea and Megara revolted. Pericles crossed over to Euboea with his troops, but was forced to return when the Spartan army invaded Attica. Through bribery and negotiations, Pericles defused the imminent threat, and the Spartans returned home.[49] When Pericles was later audited for the handling of public money, an expenditure of 10 talents was not sufficiently justified, since the official documents just referred that the money was spent for a "very serious purpose". Nonetheless, the "serious purpose" (namely the bribery) was so obvious to the auditors that they approved the expenditure without official meddling and without even investigating the mystery.[50] After the Spartan threat had been removed, Pericles crossed back to Euboea to crush the revolt there. He then inflicted a stringent punishment on the landowners of Chalcis, who lost their properties. The residents of Istiaia, meanwhile, who had butchered the crew of an Athenian trireme, were uprooted and replaced by 2,000 Athenian settlers.[50] The crisis was brought to an official end by theThirty Years' Peace (winter of 446–445 BC), in which Athens relinquished most of the possessions and interests on the Greek mainland which it had acquired since 460 BC, and both Athens and Sparta agreed not to attempt to win over the other state's allies.[48]

[edit]

Final battle with the conservatives

In 444 BC, the conservative and the democratic factions confronted each other in a fierce struggle. The ambitious new leader of the conservatives, Thucydides (not to be confused with the historian of the same name), accused Pericles of profligacy, criticizing the way he spent the money for the ongoing building plan. Thucydides managed, initially, to incite the passions of the ecclesia in his favor, but, when Pericles, the leader of the democrats, took the floor, he put the conservatives in the shade. Pericles responded resolutely, proposing to reimburse the city for all the expenses from his private property, under the term that he would make the inscriptions of dedication in his own name.[51] His stance was greeted with applause, and Thucydides suffered an unexpected defeat. In 442 BC, the Athenian public ostracized Thucydides for 10 years and Pericles was once again the unchallenged suzerain of the Athenian political arena.[51]

[edit]

Athens' rule over its alliance

Pericles wanted to stabilize Athens' dominance over its alliance and to enforce its pre-eminence in Greece. The process by which the Delian League transformed into an Athenian empire is generally considered to have begun well before Pericles' time,[52] as various allies in the league chose to pay tribute to Athens instead of manning ships for the league's fleet, but the transformation was speeded and brought to its conclusion by measures implemented by Pericles.[53] The final steps in the shift to empire may have been triggered by Athens' defeat in Egypt, which challenged the city's dominance in the Aegean and led to the revolt of several allies, such as Miletus and Erythrae.[54] Either because of a genuine fear for its safety after the defeat in Egypt and the revolts of the allies, or as a pretext to gain control of the League's finances, Athens transferred the treasury of the alliance from Delos to Athens in 454–453 BC.[55] By 450–449 BC the revolts in Miletus and Erythrae were quelled and Athens restored its rule over its allies.[56] Around 447 BC Clearchus proposed the Coinage Decree, which imposed Athenian silver coinage, weights and measures on all of the allies.[45] According to one of the decree's most stringent provisions, surplus from a minting operation was to go into a special fund, and anyone proposing to use it otherwise was subject to the death penalty.[57]

It was from the alliance's treasury that Pericles drew the funds necessary to enable his ambitious building plan, centered on the "Periclean Acropolis", which included the Propylaea, the Parthenon and the golden statue of Athena, sculpted by Pericles' friend, Phidias.[58] In 449 BC Pericles proposed a decree allowing the use of 9,000 talents to finance the major rebuilding program of Athenian temples.[45] Angelos Vlachos, a Greek Academician, points out that the utilization of the alliance's treasury, initiated and executed by Pericles, is one of the largest embezzlements in human history; this misappropriation financed, however, some of the most marvellous artistic creations of the ancient world.[59]

[edit]

Samian War

Main article: Samian War

The Samian War was one of the last significant military events before the Peloponnesian War. After Thucydides' ostracism, Pericles was re-elected yearly to the generalship, the only office he ever officially occupied, although his influence was so great as to make him the de facto ruler of the state. In 440 BC Samos was at war with Miletus over control of Priene, an ancient city of Ionia on the foot-hills of Mycale. Worsted in the war, the Milesians came to Athens to plead their case against the Samians.[60] When the Athenians ordered the two sides to stop fighting and submit the case to arbitration at Athens, the Samians refused.[61] In response, Pericles passed a decree dispatching an expedition to Samos, "alleging against its people that, although they were ordered to break off their war against the Milesians, they were not complying".ε[›] In a naval battle the Athenians led by Pericles and the other nine generals defeated the forces of Samos and imposed on the island an administration pleasing to them.[61] When the Samians revolted against Athenian rule, Pericles compelled the rebels to capitulate after a tough siege of eight months, which resulted in substantial discontent among the Athenian sailors.[62] Pericles then quelled a revolt in Byzantiumand, when he returned to Athens, gave a funeral oration to honor the soldiers who died in the expedition.[63]

Between 438-436 BC Pericles led Athens' fleet in Pontus and established friendly relations with the Greek cities of the region.[64] Pericles focused also on internal projects, such as the fortification of Athens (the building of the "middle wall" about 440 BC), and on the creation of newcleruchies, such as Andros, Naxos and Thurii (444 BC) as well as Amphipolis (437–436 BC).[65]

[edit]

Personal attacks

Pericles and his friends were never immune from attack, as preeminence in democratic Athens was not equivalent to absolute rule.[66] Just before the eruption of the Peloponnesian war, Pericles and two of his closest associates, Phidias and his companion, Aspasia, faced a series of personal and judicial attacks.

Phidias, who had been in charge of all building projects, was first accused of embezzling gold intended for the statue of Athena and then of impiety, because, when he wrought the battle of the Amazons on the shield of Athena, he carved out a figure that suggested himself as a bald old man, and also inserted a very fine likeness of Pericles fighting with an Amazon.[67] Pericles' enemies also found a false witness against Phidias, named Menon.

Aspasia, who was noted for her ability as a conversationalist and adviser, was accused of corrupting the women of Athens in order to satisfy Pericles' perversions.[68][69][70][71] The accusations against her were probably nothing more than unproven slanders, but the whole experience was very bitter for Pericles. Although Aspasia was acquitted thanks to a rare emotional outburst of Pericles, his friend, Phidias, died in prison and another friend of his, Anaxagoras, was attacked by the ecclesia for his religious beliefs.[67]

Beyond these initial prosecutions, the ecclesia attacked Pericles himself by asking him to justify his ostensible profligacy with, and maladministration of, public money.[69] According to Plutarch, Pericles was so afraid of the oncoming trial that he did not let the Athenians yield to the Lacedaemonians.[69] Beloch also believes that Pericles deliberately brought on the war to protect his political position at home.[72] Thus, at the start of the Peloponnesian War, Athens found itself in the awkward position of entrusting its future to a leader whose pre-eminence had just been seriously shaken for the first time in over a decade.[9]

[edit]

Peloponnesian War

Main article: Peloponnesian War

The causes of the Peloponnesian War have been much debated, but many ancient historians lay the blame on Pericles and Athens. Plutarch seems to believe that Pericles and the Athenians incited the war, scrambling to implement their belligerent tactics "with a sort of arrogance and a love of strife".στ[›] Thucydides hints at the same thing, believing the reason for the war was Sparta's fear of Athenian power and growth. However, as he is generally regarded as an admirer of Pericles, Thucydides has been criticized for bias towards Sparta.ζ[›]

[edit]

Prelude to the war

Pericles was convinced that the war against Sparta, which could not conceal its envy of Athens' pre-eminence, was inevitable if not to be welcomed.[73] Therefore he did not hesitate to send troops to Corcyra to reinforce the Corcyraean fleet, which was fighting against Corinth.[74] In 433 BC the enemy fleets confronted each other at the Battle of Sybota and a year later the Athenians fought Corinthian colonists at the Battle of Potidaea; these two events contributed greatly to Corinth's lasting hatred of Athens. During the same period, Pericles proposed the Megarian Decree, which resembled a modern trade embargo. According to the provisions of the decree, Megarian merchants were excluded from the market of Athens and the ports in its empire. This ban strangled the Megarian economy and strained the fragile peace between Athens and Sparta, which was allied with Megara. According to George Cawkwell, a praelector in ancient history, with this decree Pericles breached the Thirty Years' Peace "but, perhaps, not without the semblance of an excuse".[75] The Athenians' justification was that the Megarians had cultivated the sacred land consecrated to Demeter and had given refuge to runaway slaves, a behavior which the Athenians considered to be impious.[76]

After consultations with its allies, Sparta sent a deputation to Athens demanding certain concessions, such as the immediate expulsion of the Alcmaeonidae family including Pericles and the retraction of the Megarian Decree, threatening war if the demands were not met. The obvious purpose of these proposals was the instigation of a confrontation between Pericles and the people; this event, indeed, would come about a few years later.[77] At that time, the Athenians unhesitatingly followed Pericles' instructions. In the first legendary oration Thucydides puts in his mouth, Pericles advised the Athenians not to yield to their opponents' demands, since they were militarily stronger.[78] Pericles was not prepared to make unilateral concessions, believing that "if Athens conceded on that issue, then Sparta was sure to come up with further demands".[79]Consequently, Pericles asked the Spartans to offer a quid pro quo. In exchange for retracting the Megarian Decree, the Athenians demanded from Sparta to abandon their practice of periodic expulsion of foreigners from their territory (xenelasia) and to recognize the autonomy of its allied cities, a request implying that Sparta's hegemony was also ruthless.[80] The terms were rejected by the Spartans, and, with neither side willing to back down, the two sides prepared for war. According to Athanasios G. Platias and Constantinos Koliopoulos, professors of strategic studies and international politics, "rather than to submit to coercive demands, Pericles chose war".[79] Another consideration that may well have influenced Pericles' stance was the concern that revolts in the empire might spread if Athens showed herself weak.[81]

[edit]

First year of the war (431 BC)

In 431 BC, while peace already was precarious, Archidamus II, Sparta's king, sent a new delegation to Athens, demanding that the Athenians submit to Sparta's demands. This deputation was not allowed to enter Athens, as Pericles had already passed a resolution according to which no Spartan deputation would be welcomed if the Spartans had previously initiated any hostile military actions. The Spartan army was at this time gathered at Corinth, and, citing this as a hostile action, the Athenians refused to admit their emissaries.[82] With his last attempt at negotiation thus declined, Archidamus invaded Attica, but found no Athenians there; Pericles, aware that Sparta's strategy would be to invade and ravage Athenian territory, had previously arranged to evacuate the entire population of the region to within the walls of Athens.[83]

No definite record exists of how exactly Pericles managed to convince the residents of Attica to agree to move into the crowded urban areas. For most, the move meant abandoning their land and ancestral shrines and completely changing their lifestyle.[84] Therefore, although they agreed to leave, many rural residents were far from happy with Pericles' decision.[85] Pericles also gave his compatriots some advice on their present affairs and reassured them that, if the enemy did not plunder his farms, he would offer his property to the city. This promise was prompted by his concern that Archidamus, who was a friend of his, might pass by his estate without ravaging it, either as a gesture of friendship or as a calculated political move aimed to alienate Pericles from his constituents.[86]

| "For heroes have the whole earth for their tomb; and in lands far from their own, where the column with its epitaph declares it, there is enshrined in every breast a record unwritten with no tablet to preserve it, except that of the heart." |

| Pericles' Funeral Oration as recorded by Thucydides (2.43)γ[›] |

In any case, seeing the pillage of their farms, the Athenians were outraged, and they soon began to indirectly express their discontent towards their leader, who many of them considered to have drawn them into the war. Even when in the face of mounting pressure, Pericles did not give in to the demands for immediate action against the enemy or revise his initial strategy. He also avoided convening the ecclesia, fearing that the populace, outraged by the unopposed ravaging of their farms, might rashly decide to challenge the vaunted Spartan army in the field.[87] As meetings of the assembly were called at the discretion of its rotating presidents, the "prytanies", Pericles had no formal control over their scheduling; rather, the respect in which Pericles was held by the prytanies was apparently sufficient to persuade them to do as he wished.[88] While the Spartan army remained in Attica, Pericles sent a fleet of 100 ships to loot the coasts of the Peloponneseand charged the cavalry to guard the ravaged farms close to the walls of the city.[89] When the enemy retired and the pillaging came to an end, Pericles proposed a decree according to which the authorities of the city should put aside 1,000 talents and 100 ships, in case Athens was attacked by naval forces. According to the most stringent provision of the decree, even proposing a different use of the money or ships would entail the penalty of death. During the autumn of 431 BC, Pericles led the Athenian forces that invaded Megara and a few months later (winter of 431–430 BC) he delivered his monumental and emotional Funeral Oration, honoring the Athenians who died for their city.[90]

[edit]

Last military operations and death

In 430 BC, the army of Sparta looted Attica for a second time, but Pericles was not daunted and refused to revise his initial strategy.[91] Unwilling to engage the Spartan army in battle, he again led a naval expedition to plunder the coasts of the Peloponnese, this time taking 100 Athenian ships with him.[92] According to Plutarch, just before the sailing of the ships an eclipse of the sun frightened the crews, but Pericles used the astronomical knowledge he had acquired from Anaxagoras to calm them.[93] In the summer of the same year an epidemic broke out and devastated the Athenians.[94] The exact identity of the disease is uncertain, and has been the source of much debate.η[›] In any case, the city's plight, caused by the epidemic, triggered a new wave of public uproar, and Pericles was forced to defend himself in an emotional final speech, a rendition of which is presented by Thucydides.[95] This is considered to be a monumental oration, revealing Pericles' virtues but also his bitterness towards his compatriots' ingratitude.[9] Temporarily, he managed to tame the people's resentment and to ride out the storm, but his internal enemies' final bid to undermine him came off; they managed to deprive him of the generalship and to fine him at an amount estimated between 15 and 50 talents.[93] Ancient sources mention Cleon, a rising and dynamic protagonist of the Athenian political scene during the war, as the public prosecutor in Pericles' trial.[93]

Nevertheless, within just a year, in 429 BC, the Athenians not only forgave Pericles but also re-elected him as strategos.θ[›] He was reinstated in command of the Athenian army and led all its military operations during 429 BC, having once again under his control the levers of power.[9] In that year, however, Pericles witnessed the death of both his legitimate sons from his first wife, Paralus and Xanthippus, in the epidemic. His morale undermined, he burst into tears and not even Aspasia's companionship could console him. He himself died of the plague in the autumn of 429 BC.

Just before his death, Pericles' friends were concentrated around his bed, enumerating his virtues during peace and underscoring his nine war trophies. Pericles, though moribund, heard them and interrupted them, pointing out that they forgot to mention his fairest and greatest title to their admiration; "for", said he, "no living Athenian ever put on mourning because of me".[96] Pericles lived during the first two and a half years of the Peloponnesian War and, according to Thucydides, his death was a disaster for Athens, since his successors were inferior to him; they preferred to incite all the bad habits of the rabble and followed an unstable policy, endeavoring to be popular rather than useful.[97] With these bitter comments, Thucydides not only laments the loss of a man he admired, but he also heralds the flickering of Athens' unique glory and grandeur.

[edit]

Personal life

Pericles, following Athenian custom, was first married to one of his closest relatives, with whom he had two sons, Paralus and Xanthippus, but (since this marriage was not a happy one[citation needed]) around 445 BC, Pericles divorced his wife. He offered her to another husband, with the agreement of her male relatives.[98] The name of his first wife is not known; the only information about her is that she was the wife of Hipponicus, before being married to Pericles, and the mother of Callias from this first marriage.[99]

| "For men can endure to hear others praised only so long as they can severally persuade themselves of their own ability to equal the actions recounted: when this point is passed, envy comes in and with it incredulity." |

| Pericles' Funeral Oration as recorded by Thucydides (2.35)γ[›] |

The woman he really adored was Aspasia of Miletus. She became Pericles' mistress and they began to live together as if they were married. This relationship aroused many reactions and even Pericles' own son, Xanthippus, who had political ambitions, did not hesitate to slander his father.[100]Nonetheless, these persecutions did not undermine Pericles' morale, although he had to burst into tears in order to protect his beloved Aspasia when she was accused of corrupting Athenian society. His greatest personal tragedy was the death of his sister and of both his legitimate sons, Xanthippus and Paralus, all affected by the epidemic, a calamity he never managed to overcome. Just before his death, the Athenians allowed a change in the law of 451 BC that made his half-Athenian son with Aspasia, Pericles the Younger, a citizen and legitimate heir,[101] a decision all the more striking in consideration that Pericles himself had proposed the law confining citizenship to those of Athenian parentage on both sides.[102]

[edit]

Assessments

Pericles marked a whole era and inspired conflicting judgments about his significant decisions. The fact that he was at the same time a vigorous statesman, general and orator makes more complex the objective assessment of his actions.

[edit]

Political leadership

Some contemporary scholars, for example Sarah Ruden, call Pericles a populist, a demagogue and a hawk,[103] while other scholars admire his charismatic leadership. According to Plutarch, after assuming the leadership of Athens, "he was no longer the same man as before, nor alike submissive to the people and ready to yield and give in to the desires of the multitude as a steersman to the breezes".[104] It is told that when his political opponent, Thucydides, was asked by Sparta's king, Archidamus, whether he or Pericles was the better fighter, Thucydides answered without any hesitation that Pericles was better, because even when he was defeated, he managed to convince the audience that he had won.[9] In matters of character, Pericles was above reproach in the eyes of the ancient historians, since "he kept himself untainted by corruption, although he was not altogether indifferent to money-making".[15]

Thucydides, an admirer of Pericles, maintains that Athens was "in name a democracy but, in fact, governed by its first citizen".[97] Through this comment, the historian illustrates what he perceives as Pericles' charisma to lead, convince and, sometimes, to manipulate. Although Thucydides mentions the fining of Pericles, he does not mention the accusations against Pericles but instead focuses on Pericles' integrity.ι[›][97] On the other hand, in one of his dialogues, Plato rejects the glorification of Pericles and quote as saying: "as I know, Pericles made the Athenians slothful, garrulous and avaricious, by starting the system of public fees".[105] Plutarch mentions other criticism of Pericles' leadership: "many others say that the people were first led on by him into allotments of public lands, festival-grants, and distributions of fees for public services, thereby falling into bad habits, and becoming luxurious and wanton under the influence of his public measures, instead of frugal and self-sufficing".[17]

Thucydides argues that Pericles "was not carried away by the people, but he was the one guiding the people".[97] His judgement is not unquestioned; some 20th century critics, such as Malcolm F. McGregor and John S. Morrison, proposed that he may have been a charismatic public face acting as an advocate on the proposals of advisors, or the people themselves.[106][107] According to King, by increasing the power of the people, the Athenians left themselves with no authoritative leader. During the Peloponnesian War, Pericles' dependence on popular support to govern was obvious.[29]

[edit]

Military achievements

For more than 20 years Pericles led many expeditions, mainly naval ones. Being always cautious, he never undertook of his own accord a battle involving much uncertainty and peril and he did not accede to the "vain impulses of the citizens".[108] He based his military policy onThemistocles' principle that Athens' predominance depends on its superior naval power and believed that the Peloponnesians were near-invincible on land.[109] Pericles also tried to minimize the advantages of Sparta by rebuilding the walls of Athens, which, it has been suggested, radically altered the use of force in Greek international relations.[110]

| "These glories may incur the censure of the slow and unambitious; but in the breast of energy they will awake emulation, and in those who must remain without them an envious regret. Hatred and unpopularity at the moment have fallen to the lot of all who have aspired to rule others." |

| Pericles' Third Oration as recorded by Thucydides (2.64) γ[›] |

During the Peloponnesian War, Pericles initiated a defensive "grand strategy" whose aim was the exhaustion of the enemy and the preservation of the status quo.[111] According to Platias and Koliopoulos, Athens as the strongest party did not have to beat Sparta in military terms and "chose to foil the Spartan plan for victory".[111] The two basic principles of the "Periclean Grand Strategy" were the rejection of appeasement (in accordance with which he urged the Athenians not to revoke the Megarian Decree) and the avoidance of overextension.ια[›] According to Kagan, Pericles' vehement insistence that there should be no diversionary expeditions may well have resulted from the bitter memory of the Egyptian campaign, which he had allegedly supported.[112] His strategy is said to have been "inherently unpopular", but Pericles managed to persuade the Athenian public to follow it.[113] It is for that reason that Hans Delbrück called him one of the greatest statesmen and military leaders in history.[114] Although his countrymen engaged in several aggressive actions soon after his death,[115] Platias and Koliopoulos argue that the Athenians remained true to the larger Periclean strategy of seeking to preserve, not expand, the empire, and did not depart from it until the Sicilian Expedition.[113] For his part, Ben X. de Wet concludes his strategy would have succeeded had he lived longer.[116]

Critics of Pericles' strategy, however, have been just as numerous as its supporters. A common criticism is that Pericles was always a better politician and orator than strategist.[117] Donald Kagan called the Periclean strategy "a form of wishful thinking that failed", Barry S. Strauss and Josiah Ober have stated that "as strategist he was a failure and deserves a share of the blame for Athens' great defeat", and Victor Davis Hanson believes that Pericles had not worked out a clear strategy for an effective offensive action that could possibly force Thebes or Sparta to stop the war.[118][119][120] Kagan criticizes the Periclean strategy on four counts: first that by rejecting minor concessions it brought about war; second, that it was unforeseen by the enemy and hence lacked credibility; third, that it was too feeble to exploit any opportunities; and fourth, that it depended on Pericles for its execution and thus was bound to be abandoned after his death.[121] Kagan estimates Pericles' expenditure on his military strategy in the Peloponnesian War to be about 2,000 talents annually, and based on this figure concludes that he would only have enough money to keep the war going for three years. He asserts that since Pericles must have known about these limitations he probably planned for a much shorter war.[122][123] Others, such as Donald W. Knight, conclude that the strategy was too defensive and would not succeed.[124]

On the other hand, Platias and Koliopoulos reject these criticisms and state that "the Athenians lost the war only when they dramatically reversed the Periclean grand strategy that explicitly disdained further conquests".[125] Hanson stresses that the Periclean strategy was not innovative, but could lead to a stagnancy in favor of Athens.[122] It is a popular conclusion that those succeeding him lacked his abilities and character.[126]

[edit]

Oratorical skill

Modern commentators of Thucydides, with other modern historians and writers, take varying stances on the issue of how much of the speeches of Pericles, as given by this historian, do actually represent Pericles' own words and how much of them is free literary creation or paraphrase by Thucydides.ιβ[›] Since Pericles never wrote down or distributed his orations,ιγ[›] no historians are able to answer this with certainty; Thucydides recreated three of them from memory and, thereby, it cannot be ascertained that he did not add his own notions and thoughts.ιδ[›] Although Pericles was a main source of his inspiration, some historians have noted that the passionate and idealistic literary style of the speeches Thucydides attributes to Pericles is completely at odds with Thucydides' own cold and analytical writing style.ιε[›] This might, however, be the result of the incorporation of the genre of rhetoric into the genre of historiography. That is to say, Thucydides could simply have used two different writing styles for two different purposes.

Kagan states that Pericles adopted "an elevated mode of speech, free from the vulgar and knavish tricks of mob-orators" and, according to Diodorus Siculus, he "excelled all his fellow citizens in skill of oratory".[127][128] According to Plutarch, he avoided using gimmicks in his speeches, unlike the passionate Demosthenes, and always spoke in a calm and tranquil manner.[129] The biographer points out, however, that the poet Ion reported that Pericles' speaking style was "a presumptuous and somewhat arrogant manner of address, and that into his haughtiness there entered a good deal of disdain and contempt for others".[129] Gorgias, in Plato's homonymous dialogue, uses Pericles as an example of powerful oratory.[130] In Menexenus, however, Socrates casts aspersions on Pericles' rhetorical fame, claiming ironically that, since Pericles was educated by Aspasia, a trainer of many orators, he would be superior in rhetoric to someone educated by Antiphon.[131] He also attributes authorship of the Funeral Oration to Aspasia and attacks his contemporaries' veneration of Pericles.[132] Sir Richard C. Jebb concludes that "unique as an Athenian statesman, Pericles must have been in two respects unique also as an Athenian orator; first, because he occupied such a position of personal ascendancy as no man before or after him attained; secondly, because his thoughts and his moral force won him such renown for eloquence as no one else ever got from Athenians".[133]

Ancient Greek writers call Pericles "Olympian" and extol his talents; referring to him "thundering and lightening and exciting Greece" and carrying the weapons of Zeus when orating.[134] According to Quintilian, Pericles would always prepare assiduously for his orations and, before going on the rostrum, he would always pray to the Gods, so as not to utter any improper word.[135]

[edit]

Legacy

Pericles' most visible legacy can be found in the literary and artistic works of the Golden Age, most of which survive to this day. The Acropolis, though in ruins, still stands and is a symbol of modern Athens. Paparrigopoulos wrote that these masterpieces are "sufficient to render the name of Greece immortal in our world".[117]

In politics, Victor L. Ehrenberg argues that a basic element of Pericles' legacy is Athenian imperialism, which denies true democracy and freedom to the people of all but the ruling state.[136] The promotion of such an arrogant imperialism is said to have ruined Athens.[137] Pericles and his "expansionary" policies have been at the center of arguments promoting democracy in oppressed countries.[138][139]

Other analysts maintain an Athenian humanism illustrated in the Golden Age.[140] The freedom of expression is regarded as the lasting legacy deriving from this period.[141] Pericles is lauded as "the ideal type of the perfect statesman in ancient Greece" and his Funeral Oration is nowadays synonymous with the struggle for participatory democracy and civic pride.[117][142]

[edit]

See also

| |||||

[edit]

Notes

^ α: Pericles' date of birth is uncertain; he could not have been born later than 492–1 and been of age to present the Persae in 472. He is not recorded as having taken part in the Persian Wars of 480–79; some historians argue from this that he was unlikely to have been born before 498, but this argument ex silentio has also been dismissed.[20] [143]

^ β: Plutarch says "granddaughter" of Cleisthenes,[6] but this is chronologically implausible, and there is consensus that this should be "niece".[4]

^ γ: Thucydides records several speeches which he attributes to Pericles; however, he acknowledges that: "it was in all cases difficult to carry them word for word in one's memory, so my habit has been to make the speakers say what was in my opinion demanded of them by the various occasions, of course adhering as closely as possible to the general sense of what they really said."[144]

^ δ: According to Aristotle, Aristodicus of Tanagra killed Ephialtes.[145]Plutarch cites an Idomeneus as saying that Pericles killed Ephialtes, but does not believe him—he finds it to be out of character for Pericles.[36]

^ ε: According to Plutarch, it was thought that Pericles proceeded against the Samians to gratify Aspasia of Miletus.[99]

^ στ: Plutarch describes these allegations without espousing them.[67]Thucydides insists, however, that the Athenian politician was still powerful.[146] Gomme and Vlachos support Thucydides' view.[147][148]

^ ζ: Vlachos maintains that Thucydides' narration gives the impression that Athens' alliance had become an authoritarian and oppressive empire, while the historian makes no comment for Sparta's equally harsh rule. Vlachos underlines, however, that the defeat of Athens could entail a much more ruthless Spartan empire, something that did indeed happen. Hence, the historian's hinted assertion that Greek public opinion espoused Sparta's pledges of liberating Greece almost uncomplainingly seems tendentious.[149] Geoffrey Ernest Maurice de Ste Croix, for his part, argues that Athens' imperium was welcomed and valuable for the stability of democracy all over Greece.[150] According to Fornara and Samons, "any view proposing that popularity or its opposite can be inferred simply from narrow ideological considerations is superficial".[151]

^ η: Taking into consideration its symptoms, most researchers and scientists now believe that it was typhus or typhoid fever and not cholera,plague or measles.[152][153]

^ ι: Vlachos criticizes the historian for this omission and maintains that Thucydides' admiration for the Athenian statesman makes him ignore not only the well-grounded accusations against him but also the mere gossips, namely the allegation that Pericles had corrupted the volatile rabble, so as to assert himself.[154]

^ ια: According to Platias and Koliopoulos, the "policy mix" of Pericles was guided by five principles: a) Balance the power of the enemy, b) Exploit competitive advantages and negate those of the enemy, c) Deter the enemy by the denial of his success and by the skillful use of retaliation, d) Erode the international power base of the enemy, e) Shape the domestic environment of the adversary to your own benefit.[155]

^ ιβ: According to Vlachos, Thucydides must have been about 30 years old when Pericles delivered his Funeral Oration and he was probably among the audience.[156]

^ ιγ: Vlachos points out that he does not know who wrote the oration, but "these were the words which should have been spoken at the end of 431 BC".[156] According to Sir Richard C. Jebb, the Thucydidean speeches of Pericles give the general ideas of Pericles with essential fidelity; it is possible, further, that they may contain recorded sayings of his "but it is certain that they cannot be taken as giving the form of the statesman's oratory".[133] John F. Dobson believes that "though the language is that of the historian, some of the thoughts may be those of the statesman".[157]C.M.J. Sicking argues that "we are hearing the voice of real Pericles", while Ioannis T. Kakridis claims that the Funeral Oration is an almost exclusive creation of Thucydides, since "the real audience does not consist of the Athenians of the beginning of the war, but of the generation of 400 BC, which suffers under the repercussions of the defeat".[158][159] Gomme disagrees with Kakridis, insisting on his belief to the reliability of Thucydides.[152]

^ ιδ: That is what Plutarch predicates.[160] Nonetheless, according to the 10th century encyclopedia Suda, Pericles constituted the first orator who systematically wrote down his orations.[161] Cicero speaks about Pericles' writings, but his remarks are not regarded as credible.[162] Most probably, other writers used his name.[163]

^ ιε: Ioannis Kalitsounakis argues that "no reader can overlook the sumptuous rythme of the Funeral Oration as a whole and the singular correlation between the impetuous emotion and the marvellous style, attributes of speech that Thucydides ascribes to no other orator but Pericles".[9] According to Harvey Ynis, Thucydides created the Pericles' indistinct rhetorical legacy that has dominated ever since.[164]

===================================================================================

Athenian democracy

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (September 2009) |

| Part of the Politics series |

| Democracy |

|---|

| History · Varieties List of types |

| Politics portal |

Athenian democracy developed in the Greek city-state of Athens, comprising the central city-state of Athens and the surrounding territory of Attica, around 508 BC. Athens is one of the first known democracies. Other Greek cities set up democracies, and even though most followed an Athenian model, none were as powerful, stable, nor as well-documented as that of Athens. It remains a unique and intriguing experiment in direct democracy where the people do not elect representatives to vote on their behalf but vote on legislation and executive bills in their own right. Participation was by no means open, but the in-group of participants was constituted with no reference to economic class and they participated on a large scale. The public opinion of voters was remarkably influenced by the political satire performed by the comic poets at the theatres.[1]

Solon (594 BC), Cleisthenes (508/7 BC), and Ephialtes (462 BC) all contributed to the development of Athenian democracy. Historians differ on which of them was responsible for which institution, and which of them most represented a truly democratic movement. It is most usual to date Athenian democracy from Cleisthenes, since Solon's constitution fell and was replaced by the tyranny of Peisistratus, whereas Ephialtes revised Cleisthenes' constitution relatively peacefully. Hipparchus, brother of the tyrant Hippias, was killed by Harmodius and Aristogeiton, who were subsequently honored by the Athenians for their alleged restoration of Athenian freedom.

The greatest and longest lasting democratic leader was Pericles; after his death, Athenian democracy was twice briefly interrupted by oligarchic revolution towards the end of thePeloponnesian War. It was modified somewhat after it was restored under Eucleides; the most detailed accounts are of this fourth-century modification rather than the Periclean system. It was suppressed by the Macedonians in 322 BC. The Athenian institutions were later revived, but the extent to which they were a real democracy is debatable.

Contents[hide] |

Etymology

The word "democracy" (Greek: δημοκρατία) combines the elements dêmos (δῆμος, which means "people") and krátos (κράτος, which means "force" or "power"). In the words "monarchy" and "oligarchy", the second element arche (ἀρχή) means "rule", "leading" or "being first". It is unlikely that the term "democracy" was coined by its detractors who rejected the possibility of a valid "demarchy", as the word "demarchy" already existed and had the meaning of mayor or municipal. One could assume the new term was coined and adopted by Athenian democrats.

The word is attested in Herodotus, who wrote some of the first surviving Greek prose, but this may not have been before 440 or 430 BC. We are not certain that the word "democracy" was extant when systems that came to be called democratic were first instituted, but around 460 BC [2] an individual is known whose parents had decided to name him 'Democrates', a name which may have been manufactured as a gesture of democratic loyalty; the name can also be found in Aeolian Temnus,[3] not a particularly democratic state.[citation needed]

Participation and exclusion

Size and make-up of the Athenian population

Estimates of the population of ancient Athens vary. During the 4th century BC, there may well have been some 250,000–300,000 people in Attica. Citizen families may have amounted to 100,000 people and out of these some 30,000 will have been the adult male citizens entitled to vote in the assembly. In the mid-5th century the number of adult male citizens was perhaps as high as 60,000, but this number fell precipitously during the Peloponnesian War. This slump was permanent due to the introduction of a stricter definition of citizen described below. From a modern perspective these figures may seem small, but in the world of Greek city-states Athens was huge: most of the thousand or so Greek cities could only muster 1000–1500 adult male citizens and Corinth, a major power, had at most 15,000 but in some very seldom cases more.

The non-citizen component of the population was divided between resident foreigners (metics) and slaves, with the latter perhaps somewhat more numerous. Around 338 BC the orator Hyperides (fragment 13) claimed that there were 150,000 slaves in Attica, but this figure is probably not more than an impression: slaves outnumbered those of citizen stock but did not swamp them.[citation needed]

Citizenship in Athens

Only adult male Athenian citizens who had completed their military training as ephebes had the right to vote in Athens. The percentage of the population (of males) that actually participated in the government was about 20%. This excluded a majority of the population, namely slaves, freed slaves, children, women and metics.[clarification needed] The women had limited rights and privileges and were not really considered citizens. They had restricted movement in public and were very segregated from the men. Also disallowed were citizens whose rights were under suspension (typically for failure to pay a debt to the city: see atimia); for some Athenians this amounted to permanent (and in fact inheritable) disqualification. Still, in contrast with oligarchical societies, there were no real property requirements limiting access. (The property classes ofSolon's constitution remained on the books, but they were obsolete). Given the exclusionary and ancestral conception of citizenship held by Greek city-states, a relatively large portion of the population took part in the government of Athens and of other radical democracies like it.[clarification needed] At Athens some citizens were far more active than others, but the vast numbers required just for the system to work testify to a breadth of participation among those eligible that greatly exceeded any present day democracy[citation needed]. Athenian citizens had to be descended from citizens—after the reforms of Pericles and Cimon in 450 BC on both sides of the family, excluding the children of Athenian men and foreign women.[clarification needed] Although the legislation was not retrospective, five years later the Athenians removed 5000 from the citizen registers when a free gift of grain arrived for all citizens from an Egyptian king.[citation needed] Citizenship could be granted by the assembly and was sometimes given to large groups (Plateans in 427 BC, Samians in 405 BC) but, by the 4th century, only to individuals and by a special vote with a quorum of 6000. This was generally done as a reward for some service to the state. In the course of a century, the numbers involved were in the hundreds rather than thousands.

Main bodies of governance

There were three political bodies where citizens gathered in numbers running into the hundreds or thousands. These are the assembly (in some cases with a quorum of 6000), the council of 500 (boule) and the courts (a minimum of 200 people, but running at least on some occasions up to 6000). Of these three bodies it is the assembly and the courts that were the true sites of power — although courts, unlike the assembly, were never simply called the demos (the People) as they were manned by a subset of the citizen body, those over thirty. But crucially citizens voting in both were not subject to review and prosecution as were council members and all other officeholders. In the 5th century BC we often hear of the assembly sitting as a court of judgment itself for trials of political importance and it is not a coincidence that 6000 is the number both for the full quorum for the assembly and for the annual pool from which jurors were picked for particular trials. By the mid-4th century however the assembly's judicial functions were largely curtailed, though it always kept a role in the initiation of various kinds of political trial.

Assembly